One hundred years ago, Europe was the site of a revolution of languages without precedent in scale and speed in modern history.

In a matter of mere months in 1917-18, a host of languages side-lined and often suppressed in the Russian Empire – Armenian, Azerbaijani, Belarusian, Crimean Tatar, Estonian, Finnish, Georgian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Ukrainian – suddenly became vehicles for the formal declaration of sovereignty over swathes of territory. They announced the birth of the Ukrainian People’s Republic (1917-21), the Belarusian People’s Republic (1918-19), the Republic of Armenia (1918-20), and many more. Almost overnight, one after the other, each of these languages went from subordinate to authoritative, generating a new (albeit contested) political order by the very act of their enunciation in proclamations on streets and town squares, in theatres and assembly halls.

These languages do not normally figure in our conventional narrative about the ‘Russian Revolution’, which has inspired scores of commemorative centenary exhibitions and conferences over the past year. So, let’s back up and make an important clarification. What we have come to know as the Russian Revolution was neither simply Russian nor one revolution. It was in fact a series of entangled revolutions not only about land reform and economic justice, but also about national self-determination and the abuses of imperialism. From 1917, it sparked the emergence of nearly a dozen non-Russian state projects in the aftermath of empire. Most of these projects were short-lived in practice, but lasting in principle. Nearly all of them advanced liberal democratic ideals in their foundational declarations.

Naturally, the dramatic political and ideological aspects of these events have tended to attract our attention. But we would do well to explore their linguistic implications as well, especially in the aggregate. Consider it this way: before 1917, one-sixth of the world’s landmass was the domain of one official language, Russian. After 1917, it became the domain of over a dozen official languages, most of which had been denigrated under policies of russification in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. The shift was swift, and its consequences profound and far-reaching.

The declarations that brought such state projects into being are peculiar performative speech acts with illocutionary force. In the very event of their enunciation, they seek at once to change the world and to testify to that change. Here, for instance, is a key moment from Georgia’s Declaration of Independence of 26 May 1918, which gave rise to the Democratic Republic of Georgia (1918-1921):

საქართველოს ეროვნული საბჭო [...] აცხადებს: ამიერიდგან საქართველოს ხალხი სუვერენულ უფლებათა მატარებელია და საქართველო სრულუფლებოვანი დამოუკიდებელი სახელმწიფოა.

The National Council of Georgia [...] declares: now the people of Georgia hold sovereign rights, and Georgia is a completely independent state.

Successful declarations are those that materialise their message. As Searle explains in his seminal work, they ‘get language to match the world’ (1976, p. 15); or as Derrida puts it, they do what they say they do (1986, p. 8). In research on such speech acts, we tend to concentrate on their propositional content, e.g. ‘Georgia is a completely independent state’. Less often do we consider the question of the perceived status of their very languages, e.g. Georgian, which was demeaned as ‘a language of dogs’ in the late Russian Empire. Indeed, one hundred years ago, most of the declarations in question were written in languages with little internationally recognised political prestige, with virtually no longstanding role in, or association with, the administration of the modern state. They were most often written in languages dismissed by nineteenth-century imperial elites as plebeian tongues with little philosophical or political expressive potential. To alter the political landscape, they first had mountains to climb.

Ukrainian and Yiddish are two instructive examples. In the nineteenth century, Russian Minister of the Interior Petr Valuev advocated publication bans on both languages. He denied Ukrainian the very status of a separate tongue and dismissed Yiddish as mere ‘slang’, explaining that a prohibition on its use in print would ‘remove the possibility of it ever becoming the means of expression of those concepts that Jews will […] adopt from Russian and German books’, that is, from languages recognised as representative of cultural and political power (quoted in Remy 2017). From 1863, Valuev introduced prohibitions on the use of Ukrainian that aimed at nothing less than an elimination of the language from public life; roughly a decade later, his successors at the Ministry of the Interior banned the publication of Yiddish-language newspapers before embarking on a campaign against Yiddish-language schools and theatres. In the view of the tsarist regime, Ukrainian and Yiddish were meant to be confined to the private sphere with no high cultural or political currency.

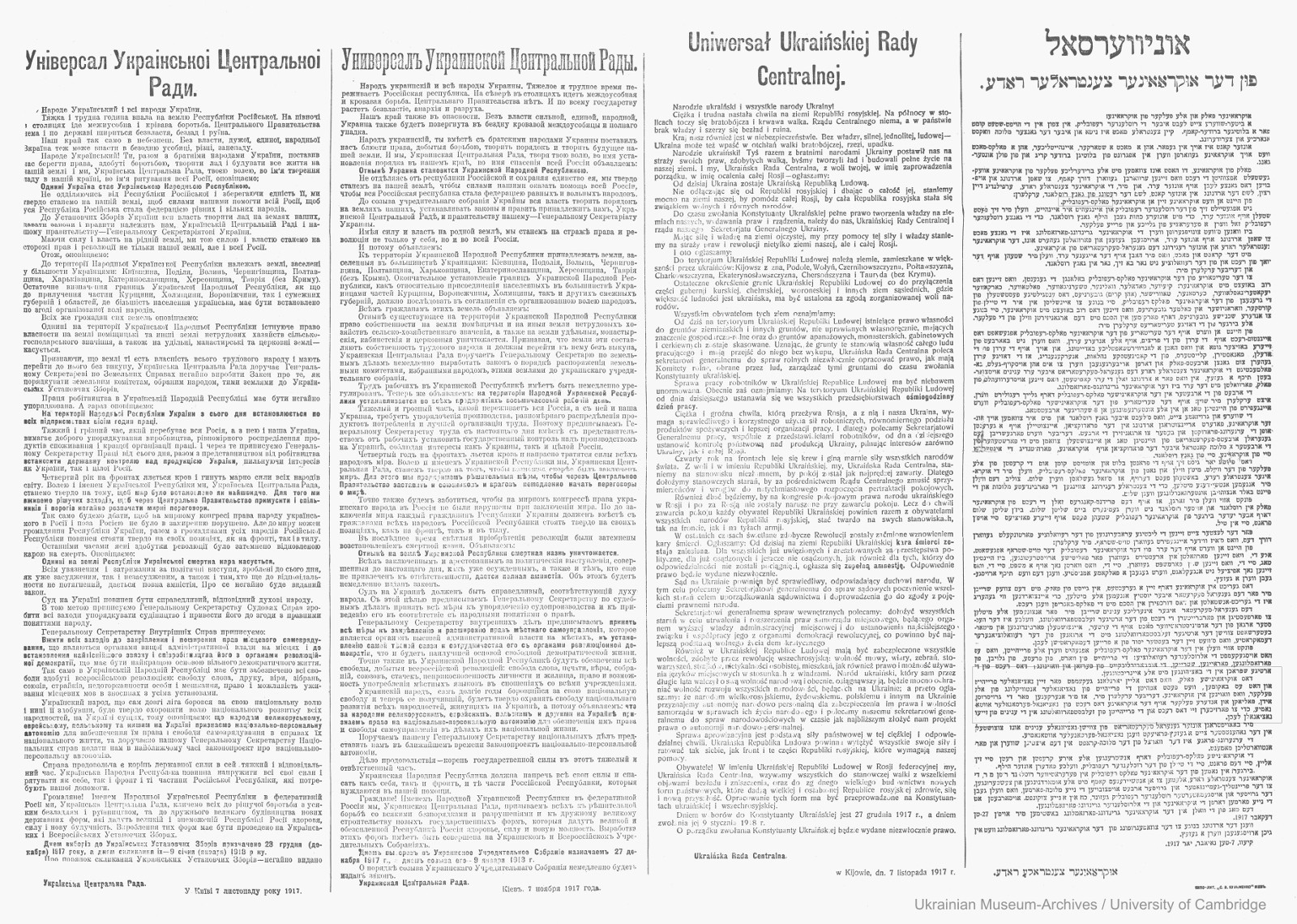

Everything changed in November 1917. With chaos cascading across the remnants of the Russian Empire, Ukrainian national democrats in the so-called Central Rada (Council) in Kyiv sought to bring order with their third decree or ‘Third Universal’, which declared the birth of a progressive, autonomous Ukrainian People’s Republic. Addressing the largest linguistic communities in Ukraine, the declaration was made not in one language, but in four: Ukrainian, Russian, Polish, and Yiddish.

The Third Universal declaring the birth of the Ukrainian People’s Republic – in Ukrainian, Russian, Polish, and Yiddish (November 1917)

(To view larger version of the image, right-click and select View Image/Open image in New Tab.)

Broadsheets of the Third Universal that place all four languages in parallel (above) are today an extraordinary, vibrant monument to this ‘revolution of languages’ of a century ago. Individual language-specific versions of the declaration were more common due to their smaller, circulation-friendly size; at least three thousand such copies were printed in Yiddish alone. This copy of the rarer, larger multilingual broadsheet comes courtesy of the Ukrainian Museum-Archives in Cleveland, Ohio, which received it along with hundreds of texts from Yevhen Bachynskyi, who served as a consul of the Ukrainian People’s Republic in Geneva. Here it appears in digital form online for the first time.

Not surprisingly, the predominant refrain in the Third Universal is ‘we declare’: ми оповіщаємо, мы объявляемъ, my ogłaszamy, ערקלערן מיר. One of its most powerful declarations is, however, completely unspoken. The multilingual broadsheet immediately makes it visible: Ukrainian and Yiddish stand with Russian and Polish as languages with impactful political resonance and state-building potential. Its parallel format, in other words, flattens the hierarchical differences in language status once operative under empire.

At the heart of the Third Universal is the concept of freedom, particularly ‘national freedom’, which was to be accorded to ‘Russian, Jewish, Polish and other peoples in Ukraine’ in the form of ‘national-personal autonomy’ ensuring ‘self-government in all matters of their national life’. The multilingual broadsheet gives this concept of ‘national freedom’ remarkable depth by showcasing it in four different senses across the four languages: національна воля, національная свобода, wolność narodowa, פֿרייַהייט נאַציאָנאַילﬠר. In Ukrainian (which also has the term svoboda as an equivalent for ‘freedom’), volia connotes a fierce, limitless freedom associated with the open steppe. In Russian (which also has the term volia), svoboda connotes a freedom that results from a relaxing of strictures and constraints. In Polish (which also has the term swoboda), wolność connotes a freedom with collective aspirations and moral consequence, akin to ‘liberty’. In Yiddish, frayheyt connotes a freedom associated with historical emancipation. For the multilingual citizen reading the broadsheet, the subtle nuances between these terms can intermingle, overlap and coalesce by way of cross-language transfer and enrich and expand understandings of the declaration’s most pivotal idea, ‘national freedom’.

Ukraine’s Third Universal and the many other political declarations driving the ‘revolution of languages’ of 1917-18 constitute a unique but understudied corpus of speech acts. Reading them as a corpus – and studying their emergence as an event in its own right – can help us come to better grips with their impressive power. Like the American Declaration of Independence, for instance, they changed the political world simply by saying so. But unlike the American Declaration of Independence, they did so while also simultaneously surmounting linguistic hierarchies meant to curb the political resonance of the very languages in which they were written. In revolutionary fashion, these declarations overachieved, and in more ways than one.

Note: comments are moderated before publication. The views expressed in the comments are those of our users and do not necessarily reflect the views of the MEITS Project or its associated partners.