“My Chinese is not good”, a heritage speaker involved in my linguistic study said with some discomfort, after finishing a Chinese reading task of the experiment. The time he spent on the task was almost twice the average, even slower than some non-heritage learners at a beginner level. However, he performed in a native-like way in listening and speaking tasks, in terms of both accuracy and reaction times. Heritage learners seem to have no problem with grammar but struggle with Chinese character recognition. They are bilinguals, but not biliterals.

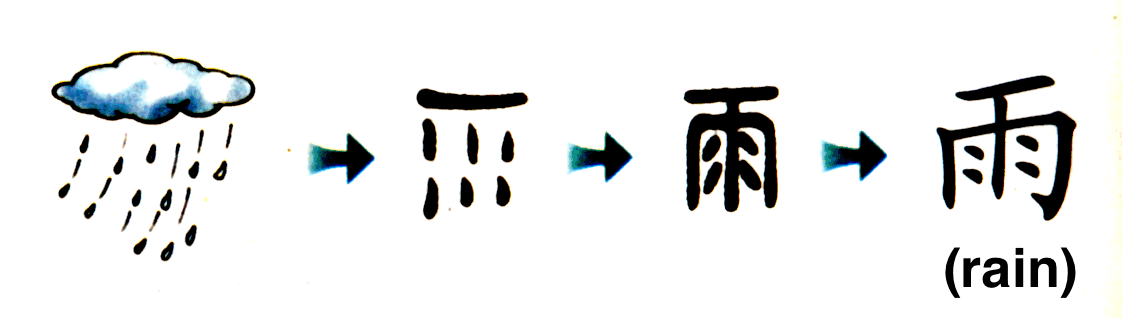

Chinese is not a phonetic language. Unlike English in which you can learn the sounds from the letters, Chinese uses a series of pictographic symbols that have specific meanings for words, with very little hints about pronunciation. Some Chinese characters simply look like the things they represent. For example, in the character “雨”, the horizontal line resembles the sky and the dots are for raindrops (see the picture below). However, many pictograms evolved over time so that the resemblance is now not that obvious, and the meanings of complex characters that involve several components (also known as radicals) are not easy to be guessed at. Chinese character recognition and production compose a main difficulty in Chinese language learning.

Generally speaking, non-heritage classroom learners correspondingly develop the ability of character recognition as they acquire linguistic knowledge of the language. On the other hand, due to the huge gap between the oral exposure that heritage learners have received from birth and the very limited exposure to the written form, heritage learners do significantly better than their non-heritage counterparts in listening and speaking but lag in reading and writing. The majority of heritage students rate their Chinese language proficiency as “good” for listening and speaking but “fair or poor” for reading and writing. It is difficult for them to estimate their own self-judgments of overall Chinese proficiency.

The well-documented asymmetry between the ability of form-meaning associations and that of sound-meaning associations in heritage Chinese learning also pose challenges for researchers and language teachers. How to elicit a heritage speaker’s real proficiency and to assess their language competence with eliminating interference from the writing system has puzzled applied linguists for a long time. In our METIS study, we found that providing pinyin (the Romanization of the Chinese characters) with the original text can effectively help heritage learners with both real-time and off-line comprehension in a test setting. In terms of teaching, Shen (2003) pointed out that heritage students who were placed in a class without non-heritage students did measurably better than when they were placed in mixed heritage/non-heritage classes. Putting heritage students in one class can enable the teacher to spend more time on writing and reading practice.

Heritage language learning is one of the focuses in our S5 project on Mandarin acquisition. We will explore developmental patterns of heritage learners and relevant confounding factors, and try to give some guidance to heritage Chinese language teaching in the UK.

References:

Shen, H. H. (2003). A comparison of written Chinese achievement among heritage learners in homogeneous and heterogeneous groups. Foreign Language Annals, 36(2), 258-266.

Note: comments are moderated before publication. The views expressed in the comments are those of our users and do not necessarily reflect the views of the MEITS Project or its associated partners.