When the cold winter is well over, I have come to visit 呼和浩特 (Hohhot) in May for my PhD project which investigates the under-researched history of teaching and learning Mandarin Chinese as a second language to Mongolian minority groups in China since 1900. Hohot is the capital of North China’s Inner Mongolia autonomous region. Its name means “Blue City” in Mongolian, a reference to the arching blue skies over the grasslands. Hohhot is a very multi-ethnic city. Han Chinese is the major group, accounting for 87 percent of the total population. Among the remaining 13 percent ethnic minority groups, Mongols are the largest, taking up around 10 percent of the total population, amounting to 286000, followed by Hui, Manchu, Dauer, Chinese Korean, Miao, Tujia, Ewenke and Yi (2010 census).

Mandarin and Mongolian are the two official languages in Hohhot. Using Mongolian-Chinese bilingual signs are regulated by law. Therefore, the linguistic landscape of the city is at least bilingual. Already at the Baita airport all signs are multilingual (Mongolian, Chinese and English), telling me: You are now in the international Mongolian autonomous region. On my way from the airport to the city centre, I came across an eye-catching concrete sculpture at the corner of the highway, which welcomes every guest from afar to Hohhot (see photo 1). It was built to celebrate the 70th birthday of the founding of the Inner Mongolia autonomous region in 2017. The statues of horses, sheep, and camels present the Mongolian nomadic pastoral culture, which brings a kind of “freshness” to the dull greyness of metropolitan life. But the Chinese central state is very present too: all the animal statues are facing the right end of the sculpture, with the Chinese slogan 在习近平新时代中国特色社会主义思想指引下奋勇前进 (‘Forge ahead under Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era’). Meanwhile, based on the left-to-right reading order in both modern Chinese and Mongolian, such presentation on the one hand acknowledges the status of Mongolian by placing it on the left, marking as the beginning, on the other hand, I wonder: Does it also implicate the shifting from Mongolian to Chinese at the end?

Photo 1: The sculpture on the airport highway

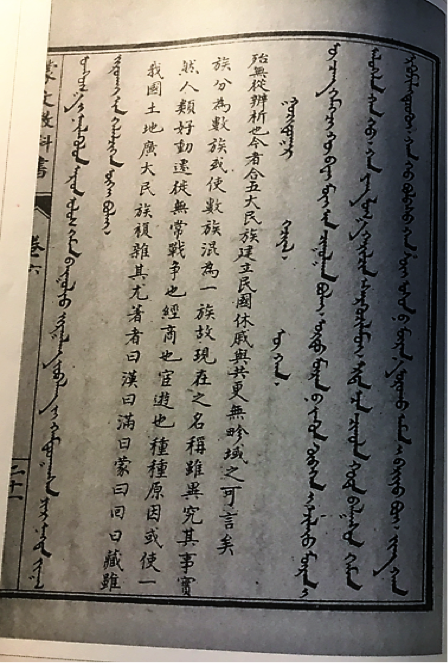

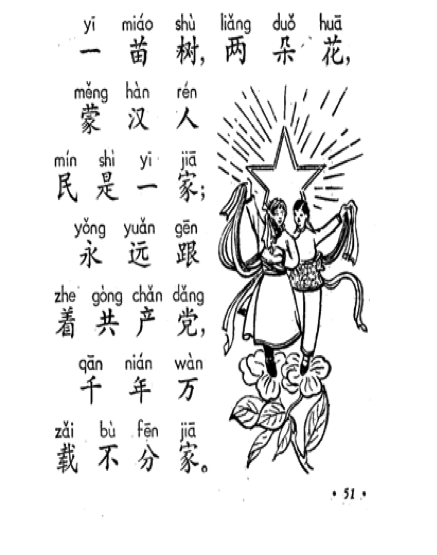

The modern history of Mongols’ Chinese learning traces back to the early 1900s. The first Chinese textbooks were authorized by the late Qing government for distribution in 1909 and included three languages, Manchu, Mongolian and Chinese, with the aim to promote mass education, disseminate western advanced knowledge, and increase Mongolians’ literacy in Mongolian, Manchu and Chinese. Since the Republican period (1912-1949), the promotion of being Chinese has been strengthened in the Chinese textbooks for Mongols, with the underlying ideology You need to learn Chinese because you are Chinese. For example, a 1923 Mongolian-Chinese textbook (see photo 2), contains a lesson titled 民族 (ethnicity) which justifies the forming of a common Chinese national identity based on five different ethnic groups, Han, Manchu, Mongol, Hui and Tibetan, the boundaries of which have blurred over the course of frequent interethnic contacts in history. After the establishing of People’s Republic of China in 1949, Mongols and Han people are portrayed as members of a big Chinese family in the textbooks (see photo 3).

Photo 2: Mongolian-Chinese textbook, volume 6 (1923)

Photo 3: Chinese textbook, volume 1 (1962)

In addition to the political reasons, Mongols are highly motivated to learn Chinese for pragmatic reasons, such as improving their employment prospects. There are not many employment opportunities for tertiary graduates who have good levels of Mongolian but possess weak Chinese competency in China. This means the Mongolian students invest more time and effort in learning Chinese. Some local Mongolian students I have chatted to called for learning much higher level of Chinese than they were required by the national language curriculum, with the aim of increasing competitiveness in the job market and erasing the stereotype that “minority people’s Chinese is poor.”

Another big impact is the decrease in education with Mongolian as the language of instruction. Although the official policy promotes ethnic minorities, by the end of 2003, 1286 Mongolian-instruction primary schools and 142 junior secondary schools had closed (IMAR Education Department, 2005, cited from Tsung, 2014). By 2010 a further decline in Mongol schools continued as they closed or were forced to become Mongol/Han joint schools (Ethnic Education Working Manual, Book 1, Ethnic Education Department IMAR, 2011, cited from Tsung, 2014).

Under the hegemony of national language and global English, protecting minority languages presents a great challenge in China and many other countries. But if not now, when?

Note: comments are moderated before publication. The views expressed in the comments are those of our users and do not necessarily reflect the views of the MEITS Project or its associated partners.